|

Dynasty

|

Period

|

Characteristics

|

| Xia & Shang | 2200 – 1100 BC |

Mythological period * Eulogized agricultural society with attendant mythology * Evidence of early divination techniques |

| Zhou | 1100 – 221 BC |

Birth of Chinese philosophy * Seven socially and politically developed states compete for supremacy. * Birth of Confucianism, Daoism and competing ideologies of the "hundred schools". |

| Qin | 221 – 207 BC |

War * Infamous & tyrannical Emperor Qinshihuang unites China for first time. * Weights, measures, roads & writing standardised. * Revolutionary books burned. * The first Great Wall built. |

| Han | 206 BC – 220 AD |

Consolidation of China as a unified state * Centralised rule & expanded state borders. * Diplomatic and commercial contact with Central Asian and neighbouring Far Eastern countries. |

| Three Kingdoms, Jin, Southern & Northern Dynasties | 220 – 581 |

Disintegration: Chaos & War * Fragmentation of successive regimes competing for power. * Buddhism introduced to China. * Famous war heroes become part of Chinese legend |

| Sui | 589 – 618 |

Re-establishment of a unified state * Re-adopt many of the Han institutions. * Restore many sections of Great Wall. * Establish Grand canal |

| Tang | 618 – 907 |

China becomes a superpower * Introduction of sophisticated judicial and administrative structures to govern the state. * Military strength assures Chinese control of the lucrative silk route. * Neighbouring Asian cultures, ideas and goods enter China. * Buddhism and the arts flourish. |

| Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms | 907 – 1125 |

China, once more, disintegrates * Anarchy, bandits and wars continue in some parts of China past the establishment of the Song dynasty. |

| Song | 960 – 1279 |

Fast-paced economic development * Warring factions unified. * Re-introduction of established government doctrine e.g. Confucianism, civil service. * Improvements in agricultural productivity and transport infrastructure. * Rise of merchant class in urban centres; introduction of paper money. * Growth in the arts. |

| Yuan | 1271 – 1368 |

Chinese are subjugated by the Mongols * The Mongol Horde sweeps through China annexing it to the world's largest, land-based empire. * The Chinese become third class citizens in their own harshly administered country. * The Mongol rulers gradually sinicised. * Despite heavy taxes, commerce grows unabated. |

| Ming | 1368 – 1644 |

Resumption of Chinese rule * Great Wall further fortified against barbarian invaders. * Eunuchs used extensively for government. * Flourishing of arts and culture. |

| Qing | 1644 – 1911 |

Chinese are subjugated for the second time * Chinese second-class citizens in their own country. * Manchu invaders initially expand the empire, reduce taxation and improve infrastructure. * As later Manchu rulers are sinicised, they become isolationist and conservative. * The European powers use gun-boat diplomacy to carve up China between them. * The Chinese become third-class citizens. |

| Republic of China | 1911 – 1949 |

Warlordism, civil war and chaos * Warlords only challenged by Chinese Communist Party and National People's Party. * Japan's 1931 invasion of China curtailed by the end of the second world war. * Chinese Communist Party wins civil war. National People's Party flees with all China's gold reserves and cultural relics to Taiwan. |

| People's Republic of China | 1949 – today |

China catching up * Communist Party, inheriting a devastated, bankrupt country, establishes the modern state. By applying the revolutionary ethic to economics, partial successes in industrialisation and agricultural productivity come at an enormous social cost. * Deng Xiao Ping, China's second leader starts to liberalise the economy in l978. This gradual process continues to this day. |

(Imperial Tours is grateful to Amir for permission to publish this excerpt from his Phd research. )

China -today the nation with the largest fleet of bicycles in the world- is surprisingly underrepresented in cycle history: we know nearly nothing about Chinese cycle history, cycle production, cycling habits or other aspects of the bicycle in China.

This contribution presents first results from historical Chinese sources, which were collected for my doctoral thesis, on China's cycle history around the turn of the century (1880s to 1920s). The article intends to give a chronological overview of the introduction and spread of the bicycle in China, from the first written account, to the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949. It takes up the question of how Chinese contemporaries of the late 19th and early 20th century perceived the bicycle, as a technically new and culturally foreign means of transportation. The paper illustrates the process of cultural appropriation in the changing terminology for the bicycle.

A chronology of Chinese cycle history

1860s. The earliest Chinese reports and official perception of the bicycle

Shortly after Michaux' construction of the pedal-driven prototype of a bicycle, and even some months before the invention became known to the European public, a selected Chinese readership learned of a new "cycling device" from the travel notes of a Chinese official. The author, Binchun, had just returned from his journey to Western Europe. As member of the first group of high-ranking Chinese officials, he had visited France, Great Britain, Germany and other nations between March and July 1866. After his return, he reported to the court on various curiosities he had discovered during his mission in the West. Among these he had seen in Paris two types of a strange device:

"On the avenues", Binchun writes, "people ride on a vehicle with only two wheels, which is held together by a pipe. They sit above this pipe and push forward with movements of their feet, thus keeping the vehicle moving. There's yet another kind of construction which is propelled by foot pedaling. They dash along like galloping horses." (Binchun, Chengcha Biji, 1866/68)

Binchun's delegation was formally sent on a diplomatic mission, but the participants had been instructed by the Chinese imperial court to investigate the latest trends in industrial development, administrative structure, and military technology. They were therefore very aware of all kinds of technical constructions. But while other technological discoveries of their visits -especially the steam engine and its mobile sister, the railway- are reported on in depth, and critically considered by the court officials with a view to their practical application towards the modernization of China's economy, the velocipede is not commented on in any known official source.

To assess the degree to which the introduction of modern technological products challenged Chinese society at the end of the 19th century and later, one has to take into account the need for industrialization and modernization in China. Military defeats and treaties after the 1840s triggered this, the Chinese saw them as humiliations, and they were closely connected to a sinking self-esteem. If in the West, technical and social change accompanying industrialization was scaring or bewildering to contemporaries, it was an intra-cultural process, growing out of its own traditions. In China, as in Japan, industrialization meant to doubt your own culture and to overcome fundamental cultural assumptions by adopting foreign ones. Attached to imported technical innovations, like the railway, gas streetlights, electricity or telephone, were, in every case, imported ideas. As such, they were seen as the materialization of modernity, foreign to China. On the other hand, parts of the Chinese elite realized the need for modernization and promoted the Western style industrialization of the country.

In this line of thinking, Chinese officials became aware of the bicycle as a practical means of transportation, only in the late 1890s, after the safety bicycle had demonstrated its potential value for military operations. With keen interest, Chinese newspapers reported on competitions between horse and bicycle in western armies, and also in Japan. For instance, the 1900-mile ride, of the 25th US-infantry battalion, from Montana to St. Louis, Missouri in 1897, was discussed in the journal Shixuebao, in regard to the possible introduction of bicycles in the Imperial army, only a few weeks after its successful completion. Whether this discussion ever came to fruition is questionable, at least there is no documentation of trial runs, or bicycle squads in China, before the early 1930s.

1870s-1880s. Cycling in the foreign settlements

Between the 1870s and the early 1890s, European and American expatriates, living in the so-called treaty ports; Shanghai and Tianjin, or in the Chinese capital Beijing, were practially the only cyclists in China. Members of these fast-growing multinational communities effectively transferred their materialistic western culture and life styles to the Far East. Like other western commodities, first introduced in the coastal cities, the bicycle came to China in the trunks of missionaries, businessmen or colonial officers, and spread from there, rather slowly as we will see, to the hinterland.

As early as November 1868, Shanghai newspapers reported on these cyclists, unfortunately only mentioning them with a few words, maybe only from hearsay. A more detailed account is given in Hu you zaji, a forerunner of modern guidebooks to Shanghai, first published in 1876. The author twice mentions foreigners cycling through the streets of Shanghai, as a spectacular sight for the Chinese visitor to the foreign settlement. Shanghai became, not only the trade hub of the region, but also a modern model city, a window to the west, which was in regard to technological development, even ahead of many European cities. It had gas streetlights lighting the main avenues (1863), public telephone booths (1882), public gardens, swimming pools and other trademarks of 19th century industrial modernization. A part of the city was established and administered from 1854 onwards as an extraterritorial foreign settlement, where the European (Victorian) life style, and the colonial social and economic institutions of its foreign inhabitants, left their imprint. Hippodromes and sports events, publishing houses, journals and newspapers, then later dance halls and department stores, are just a few examples of the numerous manifestations of modern Shanghai, which became labeled China's laboratory of modernity.

In the 1880s, the sight of ordinaries must have been familiar to Chinese, at least to the inhabitants of the foreign settlements and the capital. Cyclists were a regular theme in the Shanghai newspapers, and the pictorials of that time. The athletic capabilities and stamina of the Westerners on their ordinaries, were portrayed with admiration. On the other hand, with ironic distance, the authors expressed their amusement over the fallen cyclist. Strikingly, Chinese were completely absent from the scenes depicted. A rare exception is a cartoon from 1880, maybe the first illustration of a bicycle ever published in a Chinese journal, showing a Chinese cyclist unsuccessfully trying to ride an ordinary. The cartoon was printed in the journal Huatu Xinbao (The Chinese Illustrated News), a missionary periodical which circulated mainly in the small Chinese Christian communities of eastern China. In the explanatory text to the illustration, readers learn that "Westerners ride a small vehicle with great enthusiasm. It is not pushed or pulled forward, but managed by foot-pedalling and is called bicycle (jiaotache); it can buzz along like the wind, faster than a horse-drawn cart . but only when you have enough practice in using it." The young Chinese cyclist, though trying to partake of the Westerners' passion, not only runs his machine into a pond, worse than that, he is losing face in front of two Chinese onlookers.

Even if the journal generally intended to give its readership "religious intelligence and secular news . on such objects as history, biography, travels, the manners and customs of different nations, the various sciences, rail-roads, education, telephones, telegraphs, etc.", in the case of cycling it discouraged Chinese from this unfamiliar exercise. By hinting at the disgrace of the unfortunate cyclist, the text is probably pointing to the biggest cultural obstacle to the spread of the bicycle in 19th century China. Compared to Europe in the 19th century, for the tiny segment of Chinese society which could afford to purchase a bicycle, it was considered absolutely disgraceful to be seen pedalling through the streets, mounted on a machine, always in a delicate situation leading to a state of exhaustion. The wealthier Chinese was hardly ever seen walking in public. He was carried in a sedan chair or -if he made allowances to modern times- was pulled in a rickshaw, first introduced to China in 1874.

Individual mobility, or more to the point, adequate ways of commuting in public, was defined according to social lines, somewhat comparable to early 19th century Europe. The bourgeois or petty bourgeois of the cities went by rickshaw, due to cheap labor commonly available for low fees. Those who could not afford to rent or even own a rickshaw would mostly sit in specially constructed wheelbarrows with seven other passengers, quite common throughout the 19th century, and in use as late as the 1950s. As late as 1926, a university professor in Beijing confessed in a letter to a journal's editor, that to save transportation costs, but also to comply with social expectations, he usually called a rickshaw to pick him up, walked most of the distance, then took another rickshaw to reach his destination gracefully.

The beginnings of Chinese cycling and the first commercial ads in Chinese newspapers at the turn of the nineteenth century

The first Chinese cyclists appeared on the scene in the early 1890s. They were Chinese students; journalists or businessmen who had returned from abroad and brought their bicycles back with them. Another group were the sons of wealthy families with ties to the US and Europe. Even though they represented only a tiny portion of Chinese society, they caused a qualitative turn in Chinese cycle history. In contrast to the old elites, more and more western-educated Chinese, breaking with traditional values, were not reluctant to display their progressive cultural orientation in public. That the Chinese elite showed itself generally receptive to modern western commodities, is documented in the detailed import statistics of the Imperial Maritime Customs. As a British Customs officer comments in 1901:

"Among the officials and wealthier classes of Chinese there has, perhaps, been of late a tendency to appreciate such foreign luxuries as arm-chairs, sofas, spring-beds, etc., but it is doubtful whether there is any real or extended taste for these articles. Purchased as novelties very often, they doubtless in many cases come to be regarded as "curios", and are kept for show rather than use."

Soon after their availability, gramophones, photographic equipment and other technical devices were bought by the upper class, and used to exhibit the progressiveness of their owners. To cope with this complex cultural dilemma, a rough simplification was coined in the commonly used 19th century formula: "Chinese knowledge as a basis, western technology for practical use" (Zhongxue wei ti, xixue wei yong). After all, modernity of lifestyle, or consumption and use of modern foreign goods, was for Chinese at the turn of the 19th century, not a purely private statement, but an expression of alienation. This concept is of special relevance to the use of the bicycle, more so since cycling is a public statement, in contrast to many other technological commodities. The first commercial bicycle ads published in 1897/98, in the newspapers of Shanghai and Tianjin, addressed this thin layer of Chinese consumers. The bicycles offered are imported high quality bicycles, often racing bikes.

Also in 1897, the official import statistics (Imperial Maritime Customs) list, bicycles and bicycle parts, as a separate entry for the first time. The value recorded, approx. £10,000, would be the equivalent of 500 to 800 bicycles. In the city of Suzhou, only a few hundred kilometers from Shanghai, and commercially well connected, traffic rules of 1899 prohibited cycling in the narrow lanes, which I would interpret as a precautionary step by the municipal council, not as an indication of the mass use of bicycles. The first step in commercialization of the bicycle trade coincides with the wide newspaper coverage given to the arrival in China of the British cyclists, Lunn, Lowe and Fraser. The Chinese readership of various newspapers followed their journey from its start, in summer 1896. When they arrived in Shanghai, just before Christmas, several hundred local cyclists accompanied them on their tour through the city.

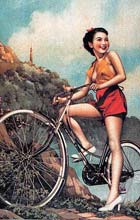

After the turn of the century, newspaper ads appeared more regularly, and the products offered are more diverse. British, American and German racers, standard bikes for men, women, and children, and transport bicycles, are now obtainable at lower price. In May 1902, an exhibition of British bicycle producers was held in Shanghai, to open the market in the place, which had already become the bicycle city. The market for bikes, which were about 40% more expensive in China than in their country of origin, was limited to the nouveau riche of a few harbour cities. Another group of potential buyers was the numerous prostitutes in the treaty ports: these "sing-song girls" not only had a relatively high income at their disposal, but also enjoyed a life free from most social constraints.

After the turn of the century, newspaper ads appeared more regularly, and the products offered are more diverse. British, American and German racers, standard bikes for men, women, and children, and transport bicycles, are now obtainable at lower price. In May 1902, an exhibition of British bicycle producers was held in Shanghai, to open the market in the place, which had already become the bicycle city. The market for bikes, which were about 40% more expensive in China than in their country of origin, was limited to the nouveau riche of a few harbour cities. Another group of potential buyers was the numerous prostitutes in the treaty ports: these "sing-song girls" not only had a relatively high income at their disposal, but also enjoyed a life free from most social constraints.

From Shanghai, Tianjin in Northern China, Macao and Guangzhou (Canton) in Southern China, the bike only slowly reached the hinterland: Chengdu, the commercial center of Western China, with 1.5 million inhabitants, counted for exactly seven bikes in 1904, three of which were owned by foreigners, three by different governmental institutions, and only one which was privately owned by a Chinese. In the 1910s, the trade network of Shanghai and Tianjin importers slowly expanded further inland. Due to high import prices and an unequal distribution of income, the bike was still a commodity affordable only to the upper 10,000 in the commercial cities. Many other Chinese cities first saw bicycles only in the 1930s and 1940s.

High prices restricted the availability of the imported bicycle to a thin layer of the higher social strata. Cycling was a phenomenon of the western-oriented upper class. Democratisation of cycling thus did not set in until the 1920s. Cultural and social changes in the preceding decade, after the overthrow of the dynastic government in 1911, had markedly altered the urban setting and produced new public spheres. The adoption of the western calendar and a regular six-day working week, formally in 1907 but first practiced by all urban enterprises and governmental institutions in the 1920s, was felt especially on Sundays. Parks were constructed or opened to the public, and American movies were shown in the theatres of all major cities. At first, the growing urban middle class discovered the bicycle as a toy for their leisure time activities. In Shanghai, with 2 million inhabitants, 9,800 bikes were counted in 1925. Their number rose to over 20,000 in 1930.

High prices restricted the availability of the imported bicycle to a thin layer of the higher social strata. Cycling was a phenomenon of the western-oriented upper class. Democratisation of cycling thus did not set in until the 1920s. Cultural and social changes in the preceding decade, after the overthrow of the dynastic government in 1911, had markedly altered the urban setting and produced new public spheres. The adoption of the western calendar and a regular six-day working week, formally in 1907 but first practiced by all urban enterprises and governmental institutions in the 1920s, was felt especially on Sundays. Parks were constructed or opened to the public, and American movies were shown in the theatres of all major cities. At first, the growing urban middle class discovered the bicycle as a toy for their leisure time activities. In Shanghai, with 2 million inhabitants, 9,800 bikes were counted in 1925. Their number rose to over 20,000 in 1930.

The bicycle entered into many aspects of life, not only privately but also due to its use by public institutions. Many Chinese may first have been equipped with bicycles as postmen, soldiers, or as members of modern police squadrons. But also, on the other side of Chinese society, the usefulness of the bicycle, for the fast and flexible transport of goods, was highly appreciated when rice was rationed in 1941/42. During the Japanese occupation of Shanghai, smugglers brought in quantities of rice on their bicycle racks.

In the 1930s, the Chinese cycle industry came into being. Nearly synchronously, the three largest importers of bicycles Tongchang Chehang (Shanghai), Changcheng (Tianjin), and Daxing (Shenyang) established their production lines. Starting around 1929/1930, with the assembly of manufactured and imported cycle parts, the enterprises grew rapidly. The combined output of the Chinese bicycle industry reached 10,000 units annually between 1937 and 1945. By the mid-1930s, Chinese cycle history reached a stage comparable to that of Western Europe around the turn of the last century. A rapid increase in numbers of cyclists in the larger cities can be observed shortly after mass production was taken up. Prices now finally reached a level, which brought the bicycle within the reach of a wider population. The number of bike owners in Shanghai (3.5 million inhabitants) constantly increased to 230,000 in the late 1940s. China-wide, there may have been half a million bicycles in 1949.

The year 1949 marks a pivotal year, not only for Chinese national history, but also for cycle history. After 1949, when the People's Republic of China was founded, the bicycle soon found a strong advocate in the communist government. Whether problems in the building of a public transport system, adequate to the needs of a "socialist" society, were the practical arguments for the endorsement of bicycle traffic, or whether there were ideological reasons, may be left to further research. As a matter of fact, the bicycle received strong support by the Chinese government in different ways: the cycle industry, which was established by merging smaller manufacturers into larger national firms, was given preferential allowances of rationed materials. The nascent bicycle industry thus was able to accomplish growth rates of 58.7% annually -ambitiously charted out in the first Chinese Five-Year-Plan. The level of one million bicycles was reached in 1958. Bicycle lanes became part of urban street planning and commuting workers received financial subsidies when purchasing a bicycle.

To conclude the development, up to the founding of the Peoples' Republic of China in 1949, we can define three stages:

1) There are four decades (from 1870 to 1910), when the bicycle as a technological object was known and reported on by the press in China, at least in the larger cites, but hardly any Chinese were using it.

2) For the following three decades, bicycle traffic increased, but stayed on a comparatively low level. Cycling was limited to the coastal commercial centres with a strong foreign influence.

3) Only with the establishment of a domestic bicycle industry in 1930 and succeeding price cuts, the use of bicycles slowly increased and became widely disseminated geographically.

The spread of the bicycle as a common means of transportation was further fostered, after the foundation of the People's Republic of China, by subsidies to the cycle industry and to cycle users.

Today's ubiquity of the bicycle in China has led to the widespread assumption of a cultural inclination of Chinese to bicycling. A deeper investigation into pre-1949 cycle history unveils quite a different image: it seems that economic and modern infrastructural reasons, rather than cultural preconditions, can explain China's development into the bicycle nation of the 20th century.

Today's ubiquity of the bicycle in China has led to the widespread assumption of a cultural inclination of Chinese to bicycling. A deeper investigation into pre-1949 cycle history unveils quite a different image: it seems that economic and modern infrastructural reasons, rather than cultural preconditions, can explain China's development into the bicycle nation of the 20th century.

The changing terminology

Together with the automobile, the bicycle holds an exceptional place in the modern Chinese vocabulary for foreign technical objects: while in most cases Chinese terms for new technologies, e. g. railway, steam engine, telephone, or the electric light-bulb, were coined shortly after their discovery and haven't changed until today, the different terms used for the bicycle, permanently switched from one semantic field to the next. No less peculiar, but more revealing in regard to the low relevance the early Chinese authors gave to the bicycle, is the fact that it took one decade to linguistically incorporate the bicycle. In Binchun's (1866) account of Parisian cyclists, the velocipede figures as an anonymous technical artifact, which is described rather in a cursory way. Although later authors refer to his text, and some even witnessed cyclists themselves when visiting Europe, none of them explicitly named the object. A transliteration of velocipede into Chinese weilouxibeida (1868) is the first step in overcoming the attitude of speechlessness towards the bicycle. But the pure phonological transcription, by reflexively combining Chinese syllables (here: virility; building; hope; north; achievement) is a rudimentary construction, which may have only added to the estrangement of the Chinese speaker, and doesn't give any sense to the alien object.

The linguistic acculturation of the bicycle happened years later, in the early 1870s, when the expression jiaotache was found. It is drawing on the older and familiar verb jiaota, which up to then was exclusively used for the specific motion of stepping on the pedals of a foot-driven water pump or mill. Appended to it was the generic term che, standing for all kinds of vehicles. Interestingly, the same word jiaotache came into use for another new machine, introduced to Shanghai in the 1870s from Britain, the pedal-driven spinning machine. On the one hand, the activity of cycling/pedaling is appropriately circumscribed, but on the other hand, it stresses the connotation of physical exhaustion at the expense of the other aspect of the bicycle: spatial mobility. Jiaotache evidently proved to be a fitting expression and was widely used next to other neologisms throughout the late 19th/early 20th century (in Taiwan, it continues to be the colloquial word for the bicycle).

It took more than two decades, before the modern term zixingche was coined. The earliest source known to me is a newspaper article of 1896). From then on, zixingche was not only synchronously used with jiaotache, but became the most common expression for bikes, which it still is today in the People's Republic of China. With zi (self), xing (vertical, linear movement) and che (vehicle), it is completely figured around movement and motion. To the ears of a Chinese living around the turn of the century, it must have been a word with a pronouncedly modern complexion. Sporadically, in the early period of their appearance in China, zixingche was also used for motorbikes or automobiles.

In the 1890s, when the modernization programs of the Meiji-era in Japan fully unfolded and made Japan the most fascinating model, and at the same time the most feared threat to China, Japanese loanwords became popular in China. Zizhuanche (Japanese jitensha) probably was introduced by the numerous Chinese students returning from Japanese universities. Linguistically, the zizhuanche is a close relative to zixingche (only the middle syllable exchanged for rotation). The word rapidly disappeared from the Chinese vocabulary, after Japan turned to more aggressive politics against China. With parts of Chinese territory invaded or threatened by Japan, and Japanese products proving to be successfully competing for Chinas market share, anti-Japanese attitudes grew.

A curious and short-lived alternative term was the modernistic baixike or baike, which came into fashion after the turn of the century. By creating new phonetic transcriptions of (American) English expressions, it was mostly the young people of Shanghai who stressed their Americanised life style, i.e., Chinese modeng for modern. On all levels of speech, the word baixike demonstratively and deliberately reveals the anti-traditionalism of the speaker. But in contrast to the older weilouxibeida, the speaker shows rather his receptiveness for, and familiarity with, the object.

Also rooted in the colloquialisms of urban youth is danche (single; vehicle). Originally, it was a synonym for the common single-wheelbarrow. In the 1940s, it appeared in modern youth literature with the meaning bike. Today it is an argot expression for the unhappy bachelor -used for instance in the original title to the Chinese movie Beijing bicycle: Shiqi sui de danche (A Single Man Aged Seventeen).

The affinity with the bicycle finally is expressed in the allegory of the iron horse – tiema (iron; horse). With reference to the animal, it expresses the possibility of an affectionate relationship -which today's half billion Chinese cyclists undoubtedly have.

© January 2004 Amir Moghaddass Esfehani

This article appeared in: Andrew Ritchie and Rob van der Plas (Eds.), Cycle History 13. Proceedings, 13th International Cycling History Conference. San Francisco: Van der Plas Publications 2003, S. 94-102.

cloisonné

snuff bottles

lacquerware

jade

seal carvings

silk

carpets

kites

After reviewing the craft subjects below, enjoy photos of crafts products in our Shopping Showroom .

Since 1904 when a Chinese cloisonné vessel won first prize at the Chicago World Fair, cloisonné has appealled greatly to foreign tastes. Developed during the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) and perfected during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), cloisonné objects were originally made for use by members of the Imperial Palace.

The cloisonné process consists of casting bronze into various shapes to which copper wire is affixed in decorative patterns. Enamels of various colors are then applied to fill in the "cloisons" or hollows, after which the piece is fired three times. Finally, the piece is ground and polished to achieve a delicate luster and smooth surface. Today, cloisonné are manufactured in a variety of shapes and colors, ranging from such practical objects as vases, bowls, ashtrays and pens to such decorative objects as bracelets and animal figurines.

Snuff bottles were not indigenous to China, but were introduced from the West by the Italian Jesuit priest, Matteo Ricci, during the early seventeenth century. However, the art of painting the interior surfaces of the snuff bottles was a Chinese embellishment to this European craft. The story of how this tradition developed describes a Qing dynasty (1644-1911) official who, upon finding that his snuff bottle was empty, used a slender bamboo stick to scrape off whatever powder was left on the interior wall of the bottle. A monk, noticing that the bamboo stick left lines visible through the transparent wall of the bottle, came up with the idea of drawing entire paintings onto the interior surface.

Painted snuff bottles are mostly made of glass, although jade and crystal agate are used to make the most precious ones. These tiny objects, often no more than six to seven cm in height and four to five cm in width, are made by first forming a flat bottle and then filling it with iron sand so as to create a smooth, milky-white interior surface. After removing the excess sand, the minutely detailed painting is applied using a bamboo brush whose tip is bent. As the necks of the snuff bottles are often extremely narrow, painting the elaborate decorative schemes of flowers, birds and landscapes or of historical and legendary scenes requires both a great deal of patience and skill.

Remnants of lacquerware have been found in Zhou dynasty (11th century-476 BC) tombs, attesting to the long history of this craft. Lacquer is a natural substance obtained from the sap of the lacquer tree, a tree indigenous to China. Up to a few hundred layers of lacquer are applied to an object's surface in order to attain the final thickness of between five and eighteen mm. After the lacquer has dried, the object is decorated by carving various designs into the surface. While traditional imperial lacquerware came in the form of chairs, screens, tables and vases, today one can find objects ranging from trays, cups and vases to small decorative boxes.

The Chinese appreciation of jade dates as far back as the Shang and Zhou dynasties (16th century-476 BC) when jade carvings in the shape of discs or cylinders were placed inside tombs. Later, during the Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD), entire suits of jade were made to cover the body of the deceased. Jade is thought to possess magical and life-giving properties and was considered to be a protector against disease and evil spirits. It is also thought to symbolize characteristics of nobility, beauty and purity.

Today jade is used to create a variety of objects ranging from dishes and ashtrays to such decorative objects as jewelry, animal figurines or elaborate tree formations. While colors vary greatly, the most precious are those in shades of white, green, brown or those with variegated coloring. An ancient story which tells how King Zhao of Qin once offered fifteen towns in exchange for a famous piece of jade shows the value that the Chinese place on jade.

The earliest seal carvings date back some 3,700 years when oracle inscriptions were cut into the surfaces of tortoise shells. Considered with painting, calligraphy and poetry one of the "four arts" of the accomplished scholar, seal carving is an art that is unique to the Far East. Unlike the West where handwritten signatures suffice, in Asia, from imperial times to today, seals are used to officiate documents, show ownership or sign a work of painting or calligraphy.

Seals are made from a variety of materials such as stone, wood, metal and jade as well as in a wide range of shapes and sizes. The surfaces of the seal are either left bare or carved with calligraphy or pictures, with one end left to carve the name of the owner. These days carvers will select a Chinese name for the foreign visitor, adeptly carving the object for its new owner. When purchasing a seal, don't forget to buy the red ink paste used with the seals.

Although the exact date for the invention of silk is still debated, it is said that it was the Empress Xi Ling who started the tradition in the year 2,640 BC. Silk itself comes from the cocoon of the Bombyx mori, an insect indigenous to China. The threads of six or seven cocoons are needed to produce a single fiber strong enough to endure the subsequent weaving process. After weaving, the silk is sent to factories to be dyed or made into cloth, carpets or embroidery.

Today, the best silks are produced in Zhejiang province, particularly in Suzhou, as well as in Guangdong and Sichuan provinces. One can buy bolts of silk fabric in a variety of colors, designs and qualities or select from a wide selection of ready-made clothes of traditional or modern design.

Carpet-making came to China during the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) when Tibetan lamas were summoned to the capital to produce carpets for the Imperial family. Carpets vary greatly from region to region, those made in Beijing employing such traditional designs as dragons and phoenixes, longevity characters, flowers, trees, cranes and scenes from classical Chinese paintings. Most carpets available for purchase in China hail from carpet-making centers in the autonomous regions of Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang and Tibet.

Kites were invented by the Chinese over two thousand years ago during the Warring States period (475-221 BC). The earliest kites, which were made of wood, were not made for recreational but for military purposes. Stories tell of soldiers tying themselves to kites in order to survey enemy positions. Alternatively, musicians attached bamboo strips to kites to create the vibrating sounds of a string instrument. Another interesting use of kites came about during the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) when people thought that flying a kite and then letting it go would send off one's bad luck and illness.

Today kites are made in a variety of designs and materials. There are over three hundred designs including those of insects, fish, birds and written characters. The frame of the kite is always made of bamboo while the cover made either of paper or silk. The painting is generally done by printing the designs onto the paper, though some custom-made kites are hand-painted and may include such portentous designs as a pine tree and crane for longevity or bats and peaches for good luck.

The history of Chinese ceramics began some eight thousand years ago with the crafting of hand-molded earthenware vessels. Soon after, in the late neolithic period, the potter's wheel was invented facilitating the production of more uniform vessels. The sophistication of these early Chinese potters is best exemplified by the legion of terracotta warriors found in the tomb of Emperor Qin (r. 221-206 BC).

The history of Chinese ceramics began some eight thousand years ago with the crafting of hand-molded earthenware vessels. Soon after, in the late neolithic period, the potter's wheel was invented facilitating the production of more uniform vessels. The sophistication of these early Chinese potters is best exemplified by the legion of terracotta warriors found in the tomb of Emperor Qin (r. 221-206 BC).

Over the following centuries innumerable new ceramic technologies and styles were developed. One of the most famous is the three-colored ware of the Tang dynasty (618-907 AD), named after the bright yellow, green and white glazes which were applied to the earthenware body. They were made not only in such traditional forms as bowls and vases, but also in the more exotic guises of camels and Central Asian travelers, testifying to the cultural influence of the Silk Road. Another type of ware to gain the favor of the Tang court were the qingci, known in the West as celadons. These have a subtle bluish-green glaze and are characterized by their simple and elegant shapes. They were so popular that production continued at various kiln centers throughout China well into the succeeding dynasties, and were shipped as far as Egypt, Southeast Asia, Korea and Japan.

Blue and white porcelain was first produced under the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368 AD). Baked at an extremely high temperature, porcelain is characterized by the purity of its kaolin clay body. Potters of the subsequent Ming dynasty (1368-1644) perfected these blue and white wares so that they soon came to represent the virtuosity of the Chinese potter. Jingedezhen, in Jiangxi province, became the center of a porcelain industry that not only produced vast quantities of imperial wares, but also exported products as far afield as Turkey. While styles of decorative motif and vessel shape changed with the ascension to the throne of each new Ming emperor, the quality of Ming blue and whites are indisputably superior to that of any other time period.

During the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), porcelain was enriched with the innovation of five-coloured wares. Applying a variety of under-glaze pigments to decorative schemes of flower, landscape and figurative scenes, these wares have gained greatest renown in the West. In almost every major European museum, you will find either a five-colored ware or a monochromatic ware (in blue, red, yellow or pink) from this period.

The quality of Chinese porcelain began to decline from the end of the Qing dynasty as political instability took its inevitable toll on the arts. However, the production of porcelain is being revived as Chinese culture gains greater recognition both at home and abroad. In addition to modern interpretations, numerous kiln centers have been established to reproduce the more traditional styles.

According to ancient lore, when a Chinese man named Cangjie learned the divine secret of writing, the spirits were so angry that millet rained from heaven.

According to ancient lore, when a Chinese man named Cangjie learned the divine secret of writing, the spirits were so angry that millet rained from heaven.

Perhaps this was because one of the first applications of the Chinese pictograph system was in the practice of divination. This long-standing association between pictographs and the occultforces of nature helps explain the historic and continuing importance the Chinese people attach to writing and to the art of calligraphy.

On a par with painting, the art of calligraphy has gone through a long evolution resulting in the development of various styles and schools. It is generally divided into five scripts: the seal script ( zhuanshu ), the official or clerical script ( lishu ), the regular script ( kaishu ), the grass script ( caoshu ) and the running script ( xingshu ).

Zhuanshu (seal script) is the most archaic, and can be seen on oracle bones (used for divination) dating back to the Shang and Zhou dynasties (14th century-476 BC). Because of its long, developmental history however, there was great regional variation in its characters. In the above illustration for example, there are 40 different versions of the same auspicious character, shou (longevity).

L ishu (official script) was developed during the Qin dynasty (221-207 BC) in an attempt to standardize writing throughout the empire. This script can be seen on many stone inscriptions of the period. Kaishu (regular script) of which the oldest extant example dates soon after to the Wei Kingdom (220-265 AD), simplified the lishu . Its characters are the closest to the modern form, being square and architectural in style.

On the basis of the kaishu (regular script), the caoshu (grass script) was developed to allow for a quicker, more fluid style of writing. The final style, or xingshu (running script), lies somewhere between the kaishu (regular) and caoshu (grass) scripts in that at times the strokes are controlled and regular and at other times free and flowing. These are the three scripts most frequently used in modern times – master calligraphers compare them to a person standing (kaishu ), walking (xingshu ) and running (caoshu ).

An individual's writing is considered sufficiantly crucial that children are trained from a young age to perfect their writing technique. It is thought that a person's character and refinement can be gleaned from her style, the finest scripts being infused with the writer's vital, creative energy. Thus, calligraphic strokes will often be described in such organic terms as the 'bone', 'flesh', 'muscle' and 'blood' or with reference to such natural forces as 'rolling waves', 'leaping dragon', 'playful butterfly' or 'dewdrop about to fall'.

Home of the Emperor, the Forbidden Palace was constructed in accordance with the laws of geomancy or fengshui. Every element was considered according to its prescriptions, the most fundamental being the positioning of the palace along a north-south axis.

Home of the Emperor, the Forbidden Palace was constructed in accordance with the laws of geomancy or fengshui. Every element was considered according to its prescriptions, the most fundamental being the positioning of the palace along a north-south axis.

The occult art of numerology similarly played a significant part within the palace's architecture. Since odd numbers are thought to be masculine and even ones feminine, the number nine, the "ultimate masculine" number, was associated with supreme Imperial sovereignty. It is therefore employed continuously in the palace, for instance in the number of studs on the gates. Likewise, the towers guarding the four corners of the palace each have nine beams and eighteen columns. But its most conspicuous application is in the fact that the Forbidden Palace is comprised of 9,999 rooms.

A further element differentiating palace architecture from other traditional Chinese forms includes the specific designation of colored glazed tiles. While these were applied to the roofs of many aristocratic homes, the use of yellow tiles was exclusively reserved for Imperial palaces, mausoleums, gardens and temples. The association of the color yellow with the Emperor originated with the idea that the great Yellow River was the cradle of Chinese civilization. As a result yellow also represents the concept of earth in the Chinese occult universe. Green was used on palace buildings reserved for court officials, while red, signifying happiness and solemnity was generally used on doors.

Prevalent throughout the palace are elements of zoomorphic symbolism. The most apparent of these is the use of the dragon and phoenix, symbols of the emperor and empress. Omnipresent in the palace, these legendary animals have been found on objects dating back as far as three thousand years. Another frequently seen animal is the lion who guards various entrance gates. Always found in a pair, the lion on the left is male and holds a ball symbolic of imperial unity. The one on the right is female and plays with a lion cub, symbolic of fertility. As the lion was thought to be the ruler of the animal kingdom, it represented qualities of power and prestige.

Interesting also are the animal ornaments found on imperial rooftops. The mystical animal at the outermost tip was thought to be the son of the Dragon King-ruler of the sea. With powers over the waters, this animal was thought to protect the palace buildings from fire. Along the roof edges are various smaller animals, the sizes and numbers of which differ according to the rank and status of the dweller within.

![]() Before the introduction of the engine, trackers were an indispensable feature of transport along the Yangzi. These river people battled daily with the river, providing the muscle to drag 40-100 ton vessels 1500 miles from Shanghai to Chongqing up a series of treacherous gorges and against a current of 6-12 knots. Mostly men, they worked like cattle for 12 hours a day, nine days at a time, to earn enough money to feed themselves poorly and every so often escape to an opium-fueled Elysium.

Before the introduction of the engine, trackers were an indispensable feature of transport along the Yangzi. These river people battled daily with the river, providing the muscle to drag 40-100 ton vessels 1500 miles from Shanghai to Chongqing up a series of treacherous gorges and against a current of 6-12 knots. Mostly men, they worked like cattle for 12 hours a day, nine days at a time, to earn enough money to feed themselves poorly and every so often escape to an opium-fueled Elysium.

There were two types of trackers, permanent and seasonal. The permanent trackers were based in local villages along the river. It was usually these that formed the basic crews of many junks. The seasonal trackers would hire themselves out at temporary shantytowns, set up where their need was greatest along the difficult gorge-strewn reaches of the Upper Yangzi, west of Yichang. The risk of storm, the potential for sudden changes in the river's water level, the avarice of ship owners and the charged, violent atmosphere to which this brutal lifestyle tended, introduced many additional, unseen risks into what was already dangerous work.

Commonly, trackers used long ropes to drag craft upriver. Four-inch wide braided, bamboo hawsers were attached to the boat's prow. As many as 400 trackers would hitch themselves in a long series to these and, shoed in straw slippers, would listen for drum signals to direct the progress of their haul. Along some stretches one foot wide "tracker paths", the charitable donation of a wealthy merchant, had been carved into the cliff. Since these had to take into account the frequent change in water level, these tracks could be as high as 300 feet above the river. You might look out for them as you proceed through the gorges. Often however, trackers while heaving their load, had to dexterously pick their way across various-sized boulders lying along the shoreline. If a cliff stood in their way the trackers, having boarded the craft, by inserting hooked poles into nooks in the rock face, would inch the boat laboriously along the cliff.

Descent of the river, though less onerous, was equally dangerous. Trackers would now work mainly in the boat. The bow-sweep, used to direct the boat, demanded fifteen men, while each of the oars ten. In descent, far less important than propelling the boat forwards was maintaining a safe position in the fast-flowing current. For this, at particularly dangerous rapids, skilled captains were on hire, who specialized in negotiating particular set of rapids.

Many trackers drowned in the raging torrents of the Yangzi. Many more suffered from work-induced strains, hernias and other illnesses. We pay tribute to them.

"The empire, long divided, must unite; long united, must divide." So begins the historical fiction "The Three Kingdoms" with a line as recited by the Chinese Diaspora as "To be or not to be" in the West.

"The empire, long divided, must unite; long united, must divide." So begins the historical fiction "The Three Kingdoms" with a line as recited by the Chinese Diaspora as "To be or not to be" in the West.

These days many Western business schools introduce Eastern strategic thinking through Sun Tzu's treatise, "The Art of War". One imagines that there is no better primer for mediaeval battle. However, for an introduction to the Chinese conception of diplomacy, strategy and warfare, there is nothing to match the colorful and astounding "Three Kingdoms".

What is most exciting about this story is that it is as influential today as it has ever been, since even before the novel was written. If this sounds nonsensical, bear in mind that the novel was itself a shrewd synthesis of myriad plays, operas, myths and folk stories current in the early-Ming dynasty (~1360-1390). The contemporary TV shows and cartoons, dramatizing the novel for Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese and Chinese audiences are following in a dramatic tradition that has already popularized these events for centuries.

To get down to specifics: "The Three Kingdoms" recreates the period between the disintegration of the Han dynasty in 168 AD and the subsequent re-unification of China under the Jin dynasty in 280 AD. In this intervening period there arose three kingdoms, which vied to unify and control China. These were Wei – based in Northern China, Shu – based in Western Sichuan and Wu – based south of the lower Yangzi. "The Three Kingdoms" traces the numerous leaders, strategies and wars that competed for dominion.

To give some notion of the centrality of the Yangzi River to this historical fiction, it is enough merely to quote the prologue. This is in the form of a poem:

"On and on the Great River rolls, racing east.

Of proud and gallant heroes its white-tops leave no trace,

As right and wrong, pride and fall turn all at once unreal.

Yet ever the green hills stay

To blaze in the west-waning day."

The middle reaches of the River Yangzi, bordering all three kingdoms, were the inevitable focus of many battles. Before introducing the most famous battle with which the river is associated, it behooves us to first present the three kingdoms and their leaders.

Kingdom of Wei

General Cao Cao is portrayed as a super-intelligent villain. During the integration of the Han dynasty, he rises to become Regent to the last Emperor. However, his intentions are ambiguous; having consolidated power at court, effectively making the Han Emperor his prisoner, he appoints himself King of Wei. From here it is but a small step for his son to depose the emasculated last Han Emperor and proclaim himself Emperor.

General Cao Cao's is an interesting portrayal because the novel's author is opposed to his ambition to usurp the Han dynasty. At the same time though, he does acknowledge Cao Cao's brilliant military strategy and savy political maneuvering. What adds to the richness of this character is that even though Cao Cao is from a powerful family, he must battle through many adversities to reach his ultimate kingly position.

Kingdom of Shu

The novel's author favors this kingdom's claim to the Imperial throne. Thus it is this kingdom which boasts the most interesting characters.

Liu Xuande , King of Shu, is a distant blood relation of the Han emperor. He is portrayed as weighing his every decision against strict ethical values; his humanity drawing men of talent to him. His character is saved from stereotype by the complication of his oft-professed virtue far exceeding his military and political talents. His short fall as a ruler therefore lends greater powers to his ministers.

None is more central than Zhuge Liang . Politician, military strategist, administrator and shaman par excellence, this character has become an archetype. He personifies an extreme idealization of a government minister. Though the historic Zhuge Liang is widely admired for his skill, his representation in "The Three Kingdoms" is ultimately anchored in myth. Uninhibited by any limiting factor, Zhuge Liang's plans are only ever foiled by the incapacity of those around him. Considering the cunning of his ingenious schemes, it is a testament to the author's skills that this fictional character is untainted by suspicions of deviousness. (Which is certainly not the case with the real, historic Zhuge Liang.)

Apart from the above two, no introduction to Shu Kingdom could be so-called without mention of Liu Xuande's two sworn brothers, Zhang Fei and Guan Yu . The opening scene of "The Three Kingdoms" presents these three penniless warriors swearing an unbreakable allegiance of brotherhood in their pledge to deliver the weakening Han dynasty from the threat of bandits.

Zhang Fei is the epitome of military strength. Honorable, valiant, physically enormous and of prodigious military skill, his flaw is that he is driven by passion more than by thought. As the story develops, we see Zhang Fei become more cunning in his ruses. However, when his sworn brother Guan Yu is killed it is Zhang Fei's instinctual nature that brings about his own demise.

Guan Yu combines military prowess, honor and intelligence. The valiant and slightly vain Guan Yu acts as a foil to Liu Xuande, serving to justify the Confucian code of ethics that cements the foundation of the kingdom of Shu. Ultimately, it is Guan Yu's arrogance that kills him. "Know your enemey and know yourself," Sun Tzu enjoins in his "Art of War". Guan Yu ignores this precept, underestimating the cunning of his young opponent.

Kingdom of Wu

The Kingdom of Wu lay south of the lower reaches of the Yangzi. This river not only marked its northern boundary but also to some extents determined its destiny. A natural buffer, the river lent Wu great strength in defense. Any northward land attack, however, was undermined by the possibility of having its expeditionary forces cornered in battle with their backs to the river, as well as by the threat of leaving its rear exposed to an attack from a river-based force.

Sun Quan is the King of Wu. He is predominantly concerned with winning back Jingzhou, a military district he allowed Liu Xuande as part of their common attack on General Cao Cao at the famous battle of Red Cliff. Liu Xuande, who originally claims to wish to borrow this district, proves to have been disingenuous. Having secured his own Kingdom of Shu, he appoints Guan Yu as a hereditary ruler of Jingzhou. It is this duplicity that provokes Wu to attack and kill Guan Yu. Liu Xuande, the supposedly ethical ruler of Shu, saves his name from ignominy by immediately risking everything – against the advice of all his counselors – to avenge the killing of his sworn brother. He initiates a campaign, which results not only in his death but also that of his other sworn brother, Zhang Fei.

Although some attempt is made to present Sun Quan as treacherous, especially with respect to his repeated attempts to murder Liu Xuande, his foreign policy is not sufficiently aggressive to equal the malevolence of a Cao Cao. Additionally, the subsequent betrayal of Liu Xuande, partly justifies Sun Quan's originally treacherous attitude.

The Battle of Red Cliff

This Yangzi River battle is the most famous of the novel, because it results in the tripartite division of power between the three kingdoms. In it General Cao Cao's river-bound, southward drive is repelled by a coalition of Liu Xuande and Sun Quan's smaller forces.

This battle is doubly memorable because it is one of the first instances, after his introduction to the novel, that Zhuge Liang is seen to excel. Indeed so fearsome is Zhuge Liang's cunning that his ally and then boss, Sun Quan's military commander, the elderly General Zhou Yu, tries to arrange his murder and thereby protect his own kingdom of Wu from potential future aggression by this military genius. Zhuge Liang, however, has already anticipated this.

In this short space, it is not possible to recreate the brilliance of Zhuge Liang's schemes. No attempt will be made. Instead, we recommend readers to get hold of a copy of "The Three Kingdoms" and turn to The Battle of Red Cliff, which begins at Chapter 44. If you do start reading from this point, it is likely that only the passing demands for food and sleep will tear you away from the novel's thrilling, remaining chapters.

To whet your appetite, here we quote an edited description of the Yangzi. Zhuge Liang has anticipated fog for one of his stratagems. This short passage sets the murky scene.

" At times the forces of yin and yang that govern nature fail, and day and darkness seem as one, turning the vast space into a fearful monochrome. Everywhere the fog, stock-still. Not even a cartload can be spotted. But the sound of a gong or drum carries far.

It is like the end of early rains, when the cold of latent spring takes hold: everywhere, vague, watery desert and darkness that flows and spreads. A thousand warjunks, swallowed between the river's rocky steeps, while a single fishing boat boldly bobs on the wells.

The roiling, restless fog is like the chaos before a storm, swirling streaks resembling wintry clouds. Common souls meeting it fall dead. Great men observe it and despair. Are we returning to the primal state that preceded form itself – to undivided Heaven and Earth?"

The Three Gorges were so named from the late Han dynastic period (23 – 220 AD). This nomenclature groups into a set of three the numerous shoals and gorges of the Yangzi river between Wanxian and Yichang. The Three Gorges are the Qutang Gorge (8km long), the Wuxia Gorge (45km long) and the Xilong (66km long) Gorge.

The Three Gorges were so named from the late Han dynastic period (23 – 220 AD). This nomenclature groups into a set of three the numerous shoals and gorges of the Yangzi river between Wanxian and Yichang. The Three Gorges are the Qutang Gorge (8km long), the Wuxia Gorge (45km long) and the Xilong (66km long) Gorge.

The gorges are as fabled today as they have been throughout the past two millennia. Countless poets have written of the gorges’ beauty and treachery, while historians, captivated by the narration of the fictive Romance of the Three Kingdoms and other historical yarns, have designated exact positions of celebrity along its steep cliffs. Despite events tumultuous as the demise of the great General Liu Bei at Baidicheng, or as devastating to deep trenches as the completion of the Three Gorges Dam, the waters of the mighty Yangzi continue to flow indifferent to the affairs of mortals while local memory lapses into the canons of legend.

Legend applies significance to stone features that might have otherwise served as signposts for travelers punctuating the journey and renouncing the timeless water, while the linear nature of passage through the gorges provides today’s travelers a window into the country’s obsession with its own mystic heritage. “Hanging Monk Rock,” “Drinking Phoenix Spring,” “Wise Grandmother’s Spring,” “Rhinoceros Looking at the Moon,” “Beheading Dragon Platform,” and “Binding Dragon Pillar” are but a few of the monuments along the Three Gorges. Do not despair if you can’t distinguish the dragon from the cliff, instead, think of the multitude of rock formations named of grandeur as bookmarks in a narrative that defines the creation and oral history of the region.

Sailing through the Three Gorges generally requires a commitment of three days and nights, and most leisure ships departing from Chongqing will include occasional side trips along the way.

Visitors are first introduced to Baidicheng, or White Emperor City, and its current namesake owes to a Sichuan province official, Gong Sunshu. In 25AD, Gong spotted a white mist in the shape of a dragon emanating from a local well, and, in an un-rare move, proclaimed himself the White Emperor while correspondingly naming the town in his glory. Locals constructed a temple at Baidicheng to commemorate Shu, but nearly 1,500 years later it was replaced by a Ming Dynasty governor and renamed the “Three Merits Temple,” only to be replaced again by statutes of Three Kingdoms protagonists Zhuge Liang and Liu Bei and renamed “Righteous Shrine.” In another 1,500 years, it is unclear who might reside in the Righteous Shrine, if indeed it will still be called such…

Qutang Gorge

Lu You, a scholar of the Southern Song dynasty (1120 – 1279), goes into greater detail as he describes his descent:

"Entering the Qutang Gorge, I saw two rocky walls rising into the clouds and facing each other across the river. They were as smooth as if they had been cut with an axe. I raised my head and looked up. The sky was like a narrow waterfall. But there was no water falling down. The river in the gorge was as smooth as shining oil."

From "Record on Going into Sichuan" by Lu You (1170)

For thousands of years, the Qutang Gorge proved too unruly for travelers to pass without caution: at the narrowest stretches, peaks up to 4,000 feet were whittled by a river that passed only 500 feet wide. Locals during the Tang and Song dynasties constructed systems of suspended iron chains to control transit through the raging waters. Although the Qutang Gorge no longer provides such a menacing passage after the completion of the Three Gorges Dam, one can still infer the magnitude of the risk involved to traverse this gauntlet in days past.

The most celebrated feature at Qutang Gorge is known as “Meng Liang’s Staircase,” a series of deep holes evenly spaced and oddly quarried into the sheer cliff without connection at either top or bottom. Legend holds that a general in the historical novel Yang Family Generals, sought to recover the remains of General Yang Jiye located at the top of the mountain by secretly chiseling a pathway up the sheer cliff to Yang’s grave. Versions of the myth diverge, but a local monk, by chance or by duplicity, crowed like a rooster signaling the coming morning and caused Meng Liang to resign his endeavor. Infuriated by his failure, Meng Liang later gratified his ego by seizing and hanging the monk from a nearby cliff. Romance aside, archaeologists have instead identified Meng Liang’s Staircase near the site of an ancient town, and residents used it in conjunction with a series of rope-ladders to scale the cliff.

Wuxia Gorge

The character "Wu" refers to a shaman. This gorge was so called after an imperial physician called Wu Xian who lived during the time of King Yao. Wushan begins the second set of gorges, Wuxia; 45km of fantastic precipices. Don’t be alarmed if you find yourself in a sea of local tourists pursuing Wuxia’s glory: the area’s reputation has attracted countless masses for millennia.

A side trip up Danning Stream takes you through the picturesqe Lesser Three Gorges (see the photo above). Towards the end, high up on cliff are hanging coffins . A burial custom of the Ba people, dating back over 2,000 years, they resemble other cliffside coffins found in Gongxian near Yibin. These hanging coffins are said to date back to the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644). No one is sure how or why this custom came about, however the Ba people – no longer surviving – were known for other perverse behavior, such as that of protesting heaven. One such protest, for example, took the form of wearing too many clothes in summer and too few in winter.

Xiling Gorge

On the approach to Xiling, the longest and traditionally most treacherous of the Three Gorges, visitors will pass the birthplace of the 3rd century BC poet, scholar, and official Qu Yuan. Loved by many during his time, Qu was dejected from office by an imbecile king of the Chu culture. Upon learning that the Chu culture was conquered by king Ying of the Qin (who later united all of China as the country’s first emperor), poet-statesman Qu drowned himself in a tributary of the Yangzi. To commemorate Qu Yuan, his subjects fed his spirit by dumping sticky rice wrapped and cooked in leaves. For over 2,000 years have proudly commemorated Qu Yuan with an annual dragon boat festival, even if they no longer dump zongzi into rivers across the country and rather chose to ingest the delectable morsels themselves.

"The Xintan Shoal" by Su Shi (Song dynasty)

"Our flat boat skirts the winding mountains;

Astonished we are by the approaching scenery.

The white waves surge across the river,

Rising and falling like snow descending from the sky.

Each wave being higher than the preceding one,

All fall onto the depressed riverbed.

Small fish disperse and then assemble,

Appearing and disappearing as if in boiling water.

The cormorants dare not dive into the river,

They one fly across it, flapping their light wings.

The egrets wade in the shallows, slim and agile,

But sometimes they cannot stand steady.

As for people aboard the small boat,

No one dares display poor oarsmanship.

To the temple shore they go to pray for safety."

Fortunately, with the completion of the Three Gorges Dam downstream, Xiling Gorge today bears little resemblance to the words of Su Shi and one no longer must worry about his life crashing abruptly in the turbulent waters. Passage through the Xiling Gorge heralds the end of the journey before the river widens and waters become paralyzed by the Three Gorges Dam in Yichang.

The Geological Formation Of The Three Gorges

During the Triassic period, some 200 million years ago the Mediterranean Sea flowed as far east as the Yangzi River valley. When the Indochina orogenic (mountain forming) movement occurred, the western land mass fell and the Mediterranean Sea receded. Simultaneously, as the Qingling Mountains rose in central China, a system of lakes and rivers developed in the Yangzi River valley, flowing westwards to the Mediterranean. 130 million years later, the Yangshan movement took place, by which the limestone-based Sichuan Basin and Three Gorges area rose to their current location. As a result of this occurrence, it is possible in the area to find at 1000 meters altitude, pebbles and rocks belonging to lake bottoms of this past geological period.

The Himalayan orogenic movement, which followed 30 million years later (and which continue to raise the Three Gorges by 2-4 millimeters per year), gave rise to dramatic changes west of the Three Gorges: vertiginous mountains, high plateaux and deep valleys formed. At this time, two rivers flowed from a large lake in the Three Gorges area; one to the west and another to the east. Because the altitude drop in the eastern river was much greater than the one in the west, and hence its rate of erosion faster, when the two rivers eventually met to cut a precarious path through the Three Gorges, the resultant river flowed eastwards.

Effect Of The Three Gorges Dam

Since The Three Gorges are much taller than the total planned water level increase of 80 meters, they will never be submerged by the reservoir. They will however, appear to be 80 meters lower and therefore not as dramatic as they are now. Indeed, visitors should bear in mind that after the Gezhouba Dam project, completed in 1988, the water level in The Three Gorges rose by 10 meters.

The History of the Silk and Fur Roads

The History of the Silk and Fur Roads

The incursions of the Xiongnu, a savage Turkic tribe that regularly pillaged the towns on China’s northern border, prompted the Han Emperor Wudi (r. 140-86BC) to seek Western allies for a joint attack. For this military reconnaissance mission he sent out one hundred men, led by Zhang Qian, who took thirteen years to report back with tales of glittering western cities and alien cultures. As soon as he did though, Zhang Qian was sent back in charge of a still larger party equipped with ten thousand sheep, gold, satin and silk.

This second journey, China’s first substantial contact with the Central Asian civilizations, opened up caravan routes. The route that passed south of the Tianshan mountains, used primarily for the export of Chinese goods, came to be known to Europeans as Silk Road. However, another route, which passed north of the Tianshan mountains, was known in China as the Fur Road, and it was along this passage that new religions, ideas and goods were imported into China.

During the spectacular military, cultural and financial successes of the Tang dynasty (618-907) many merchants from Persia, Arabia and Central Asia were attracted to China’s capital, Changan, in search of profit. They brought their religions and fashions with them.

The Great Mosque and Muslim Quarter

As foreign communities grew in size, they introduced their own customs and facilities. The 50,000 strong Muslim community that lives and works today in Xi’an traces its history to those Middle Eastern merchants who, after travelling the Fur Road, settled down here. Then, as now, the Muslim community perpetuated their culture by operating mosques and schools. So it is that the Great Mosque was originally constructed in the year 742. Today the Muslim community, which supports ten or so mosques, runs its own primary school, foods shops and restaurants. For over 1300 years, they have been an integral part of Xi’an’s colourful daily life.